Extended version of the script from the concert to celebrate Jordans’ Centenary – written by Catriona Troth. With grateful thanks to the archive at the Jordans Estate Office for the photographs and many of the details.

This is a celebration of the Centenary of Jordans Village. But it’s impossible to tell the story of Jordans Village without going back in time to say a little bit about how Quakers came to be in Jordans at all. Because as the architect of the village, Fred Rowntree, said at the laying of the first brick:

“At the bottom of the hill they have a Friends Meeting House that has stood for 220 years, a silent testimony of the great movements of religious liberty and freedom of this country, won by those buried in its graveyard. This proposed village would not have been started but for the little meeting house and all that it means to Friends.”

Jordans Meeting – originally called Chalfont Meeting – has its origins in various Quaker homes in South Buckinghamshire where local Friends gathered. One of these was the kitchen at Jordans Farm, home of William Russell.

However, from the late 1660s, Quakers meeting to worship were at risk of prosecution under the Second Conventicle Act, which gave Justices the power to convict anyone attending a nonconformist meeting of more than five people. Informers were rife, and worshippers at Jordans farmhouse were regularly taken away to prison, or had their goods confiscated.

In 1687, James II issued a Declaration of Indulgence, suspending all laws penalising dissenters for not attending the established (Anglican) church or taking the sacraments. Many Friends were released from gaol and the Quaker Meeting at Jordans Farm took immediate advantage. Plans were made to build a Meeting House beside the burial ground – the first purpose built Quaker Meeting House.

♫

The Meeting at Jordans flourished for over a hundred years, but by 1798, a visiting American recorded: ‘Though there is a very convenient meeting house and beautiful burying ground … there are but now two ancient men to attend to keep up the meeting.’ Shortly after, the Meeting was discontinued and during the 19thC, the meeting was only used for Yearly Gatherings in the summer. We have a wonderful first hand description of one such gathering from 1869:

‘The Meeting House, itself a good-sized apartment, is soon filled; then the room upstairs is thrown open by putting down the shutters; the parlour of the cottage by taking down some framing, and soon (often to overflowing) all parts are full … A meeting for business succeeds that for worship; at the close of which a curious transformation takes place, and refreshment of all kinds for the body succeeds the instruction for the soul.

Nothing can surpass the simple hospitality now shown; the impromptu tables in the Meeting House are well filled with cold viands, and, should the day be fine, are set in the open air; all Friends are made welcome, the pedestrian is asked freely to share the substantial things the carriages have brought; and when the visitors have done, the numerous flymen, coachmen, and servants, sit down and also make their ample meal.

The long summer day leaves ample time after the repast is over to fill up the interval between its close and the start for the return, by a walk round the beautiful woodlands … By and by all return to the little estate and take a last look at the scene over a quiet cup of tea.’

♫

At the same time as Jordans Meeting was facing a decline, Quakerism in Britain was facing a new challenge – from its own young people. Younger Friends were excited by new scientific discoveries and energised to tackle the social problems they saw around them. Prompted by this new generation of Quakers, in 1895, 1300 Members and Attenders took part in a four-day conference at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, which proved to be a turning point for British Quakerism. So it was, when the opening of the railway line to Marylebone brought Quakers back to the Chilterns, and Jordans once again became an active meeting, it was a new kind of Quakerism they brought with them – more outward looking, socially idealistic and less rigid in its attitudes. In 1912, two years after the meeting was revived, Friends bought Old Jordans Farm and turned it into a Quaker hostel, and one of the farm’s orchards was made into a new burial ground. Those Friends didn’t know it, but they were about to face one of Quakerisms most difficult challenges yet.

When World War 1 was declared in August 1914, a group of Young Friends quickly proposed the idea of an ambulance unit. They were convinced that ambulance services would be woefully inadequate, so that offering such services could save many lives and enable conscientious objectors to make a vital contribution. A letter to The Friend appealed for volunteers and by early in September the first training camp for the Friends Ambulance Unit took place in the Mayflower Barn at Old Jordans.

These must have been a desperate time for Quakers, fundamentally opposed as they were to War. Yet somehow they held onto the idea that it was possible to build a better world. And when neighbouring Dean Farm came up for sale in 1916, they saw a way that might be achieved.

The first meeting of the management committee for the establishment of Jordans Village took place in Devonshire House in London on the 9th March 1916, with Frederick Rowntree as one of its leading members. They proposed buying 102 acres of Dean Farm and establishing a community with community ownership of land and co-partnership housing. By August of that year – with lightning speed, as anyone familiar with Quaker processes will agree – they had already raised £28k in capital and had a plan setting out 8 acres of woodland, 4 acres for the village green, 8 acres for forty cottages, and further plots of either 1.5, 1.25 and 1 acres each, to provide 58 leasehold houses and a total expected population of 500.

Then negotiations with the existing owner, Colonel du Pre, began.

Reading the minutes, this is where things became a little unstuck, and perhaps Quaker naivety ran into the realities of hard-headed business deals. Time and again throughout 1917, the minute book records making an offer through the owner’s agent, only to find the goal posts had shifted a little since the last correspondence. One of the sticking points appears to have been the status of the existing tenant of Deans Farm – Ebenezer Worley, known as Ebbie. Quakers seemed to take a rather dim view of him as a farmer. In Arthur Haywards’ Jordans: the making of a community Ebbie’s farming is rather uncharitably described as ‘spasmodic and ineffectual scratching of the soil.’ Nonetheless, Colonel du Pre was determined to protect his rights.

There were arguments too over electricity supply. The Quakers did not want to rely on the local supply company and so wanted to erect their own generator – something the owner was not keen on. And Jordans Village Industries was also a bone of contention. Quakers wanted to promote the establishment of “suitable industries on sound and just lines so as to give to those engaged therein scope for the growth of character, self-expression, and high standards of individual workmanship.” Industries would market-gardening, poultry- and bee-keeping, woodwork and metal industries and brick- and tile-making. But the terms of the contract with Colonel du Pre forbade the building of a ‘factory’. Did the small scale industries envisaged by Quakers constitute a factory or not?

♫

Somehow, by February 1918, agreement was finally reached, contracts exchanged and a deposit paid. Friends Ambulance Unit trainees were employed, along with some German prisoners of war, to take over cultivation of the land from Ebbie Worley and large areas were sown with potatoes and cabbages.

The timing, however, was awful. The war was dragging on. Severe defeats had been inflicted in France. And costs of materials had risen beyond all expectation. Nonetheless, Quakers believed that this made it more incumbent upon them to ensure that “certain values and principles should be enunciated all the more clearly amidst the clangour of war.” Efforts to raise money for the building of the village were renewed. One of the early investors recorded was a certain Arthur Ransome – correspondent for the Manchester Guardian and later author of Swallow and Amazons – who in July 1918 offered to lend £100 on debentures, and was repaid in 1924.

Not long after Armistice Day, 1918, as recorded in a speech given by Arthur Pickstock, the village’s original carpenter, to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the village ‘an architect, a master builder, a horticulturalist and a carpenter’ met in a freezing field in an icy cold wind to discuss what needed to be done. Those four men were Fred Rowntree, Sydney Lawson, the Master Builder, Fred Hancock, the horticulturalist, and Arthur Pickstock himself.

The scale of the job ahead of those pioneers should not be underestimated. They had to tackle the building of roads, laying drains, digging foundations, setting up workshops and offices and arranging transport of materials solely by horse and cart. The emphasis was on craftsmanship: the only mechanical device they had was a circular saw – no mechanical diggers or mixers. Everything was to be done themselves, down to making hinges for the doors.

Though labour was now plentiful, supplies and materials were in scarce and costly supply. And the task of surveying acres of virgin land was immense. Arthur Pickstock describes with feeling “the homeward plod with aching feet and backs after a day of humping a builder’s Dumpy Level around and knocking in pegs for levels and boundaries.”

They manually dug out chalk, clay, sand, flint and stone from acres of land. The chalk burned to make lime, the flint and stone was used as ballast for the roads. The clay was used to make bricks in the brick kiln.

Quakers must by then have made their peace with Ebbie Worley, the much derided tenant of Dean Farm, for it was he who provided the three-wheeled dobbin cart for transport and the horse to drive the huge pug-mill that prepared clay for the brick kiln.

The first cottage to be built around the village green was for the master builder, so that he could be based on site. We have a vivid description of the ceremony of laying of the foundation stone, which took place on February 15, 1919.

“Not less than 150 people braved the cold in order to attend the ceremony. Mr Harris opened the proceedings by producing a bottle containing a copy of that day’s Daily News, a penny of 1919, a full list of the names of the men at present engaged on the work, and a memorandum and brief prospectus describing the aims and objects of the village scheme. These contents were placed in a safe cavity in the foundation wall of the cottage and covered in mortar.

“Mr Fred Rowntree, architect of Jordans village laid the first brick, bearing the date 15/2/19, and on completion declared the brick to be well and truly laid. The second brick was laid by Miss A.L Littleboy, the third by Mrs Henry Harris, wife of the secretary, the fourth by Mrs Albert Cotterell, the fifth by Mrs Rowntree and the sixth by Margaret, the little daughter of Mr Lawson the master builder, who is the live in the first dwelling on the estate. The bricks bear the initials of those who laid them.”

Afterwards, they gathered for a meal, and Fred Rowntree gave a speech setting out the aims and objects of the village.

“The village is to be worked on Democratic lines, and there is to be no encouragement for profiteering. Everyone who has any concern in the Company will have a voice in the management of affairs. The idea is a village with groups of cottages, workshops and other buildings necessary of the amenities of village life, where suitable industries might be established on sound and just lines, with facilities for all residents to have some land for market gardening and fruit growing, a centre for training in citizenship as well as manual, agricultural and other pursuits: to enable men, women and apprentices to master a craft of their own choice under most favourable conditions, such as woodwork, carpentry, furniture making, chair making, toy making, bricklaying, plumbing painting and hand-loom weaving – and everything carried through in the right spirit, and workers would feel their work to be a joy.

“We intend not to talk about things that should be done but instead are going to carry our ideals out and put them into operation.”

♫

From this point on began “a hive of industry all around what is now the village green. The joiners shop, the sawmill, the cabinet makers shop, the blacksmiths forge, the horticultural depot, the glass and paint shop – and then the village stores, to cater for the hungering needs of the workers in the way of food and coal – to say nothing of newspapers and tobacco. It was amazing, you named it and there it was in that small front portion of the estate office.”

And even before this, when the builders’ sheds were still being put up and the walls of the Lawson’s house were only breast high, eight of the workers to establish the village’s Social Guild. It was built in six weeks, by voluntary labour, and opened in October 1919.

The front page of Guild’s Constitution declares that it is “for the workers of Jordans Village and their wives” (though later in the constitution’s rules, that’s amended to the more egalitarian ‘and their wives and husbands’!). Its motto was ‘Each for all and all for each’, once inscribed on a plaque in the Guild Hall which has since gone missing. The Guild provided (among other things) a cycle club, football club, cricket club, tennis courts, lectures, concerts and outings – as well as something that would make us cringe today, the Black Diamond Minstrels.

In February 1920, on the anniversary of the laying of the first bricks, the daughters of Bert Cheston and Sydney Lawson planted a chestnut tree, which still stands today on the corner of the green. From there on, steady progress was made towards realising those ideals first formulated in the midst of war. The first village newssheet – the Penn Pioneer – was published in 1920. The village school opened in 1922.

♫

Sadly, Quakers hadn’t bargained for post-war inflation, which drove up the costs and made it impossible to carry out the more expensive, individually crafted building methods. In 1923, Jordans Village Industries was forced to go into voluntary liquidation. This was the end of the concept of Jordans as a utopian community of artisans and workers. It was also very nearly the end of the village shop, which had been taken over by William Hughes in 1922. Thankfully, with £220 raised by village residents, Jordans Cooperative store was born, taking shape in a shed in front of the village hall.

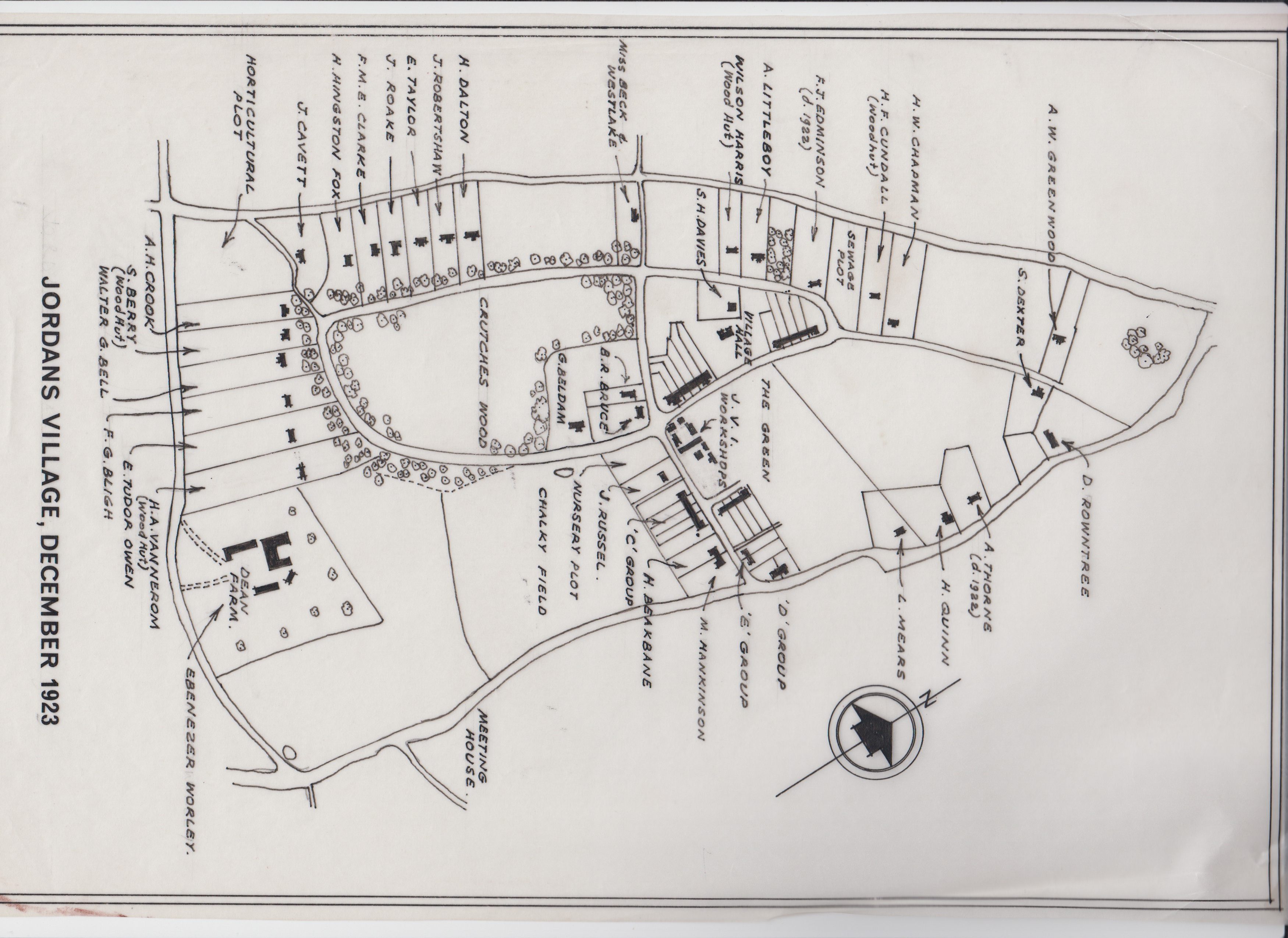

Jordans Village Ltd, however, had been registered as a Friendly Society in 1920, and it survived. By 1923, the terraced cottages around the Green designed by Fred Rowntree, were completed and occupied. And Jordans as a living residential community could be said to have really begun.

In 1933, a Penn Pageant was held (the first of several William Penn commemorations held over the years). This one included a reconstruction in full costume of the Penn Mead trial, performed outside the Mayflower Barn (with a rather larger cast than the one-man show seen here last year!)

The music club was started in the early summer of 1944. It was the brainchild of musician Joyce Cook, which come to live in Jordans in 1938 with her friend Sylvia Brown. In 1940, they bought Chelsey Cottage in order to start a market garden on a plot next to School Lane, where they kept goats, hens and geese – and housed the pigs belonging to the Jordans Pig Club, which flourished during the War.

In 1944, London was being battered by the V1 Flying bombs, something which almost but not quite postponed the Music Club’s first concert, given in the Refectory by the Blech String Quartet. Other wartime performers included the Griller String Quartet (who were billeted at the time in Three Households, Chalfont St Giles) and Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten. Later concerts were held in the Mayflower Barn, which with its lovely garden made a unique and beautiful setting for the concerts – much admired by visiting artists, although the acoustics were said to be not always of the best! English conductor Reginald Jacques was a resident of Jordans at the time. He brought his orchestra to play at Jordans several times, as well as establishing a connection with the management agency, Ibbs and Tillett, who were able to engage many distinguished musicians to play, including the Amadeus Quartet, Elizabeth Schwartzkopf, Yehudi and Hepzibah Menuhin. One or two concerts described as ‘off-beat’ are also recorded, including Walton’s Facade, and a harmonica performance by Larry Adler.

♫

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, the flats at Puers Field were built –once the site of the brick kiln where the bricks and tiles for all the cottages were made. A later block of flats was constructed at Cherry Tree Corner in the late 1960s. The latest addition to the village’s buildings is four retirement cottages completed and occupied in 2009. And over the years, a number of open spaces have been preserved to retain the original character of a garden village: Chalky Field in 1923, the Village Green and Crutches Wood in 1934, and Cherry Tree Corner in 1940.

The village continues to be run as a self-governing community. The freehold of roughly half the properties is still held by Jordans Village Limited, which leases them to tenants and leaseholders.

What is it that is needed to build a community? Those who come together in those post-war years believed they knew. It requires the residents of the village to have a voice in what happens within it. It requires a shop and a school. Shared spaces inside and out to bring people together. And shared activities – sporting, artistic or simply social.

All those things are still present in Jordans today. The shop has been extended several times, and survives and thrives as a community shop supported by volunteers from the village. Children can still attend school in the village up to age 8. The village fair and Music on the Green take place annually on the green space laid out all those years ago, while that so-called ‘temporary’ village hall, erected by the workers in just six weeks, is still hosting events from the Christmas Party to the Village Supper, as well as providing a home for the village’s nursery. And as for the democratic ideals of that committee that met in 1916, they are still embodied in Jordans Village Ltd and the Tenant Members Committee.

Jordans is still alive and well at 100. I think Fred Rowntree would be proud.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.